Scientific research is key to tackling the climate crisis.

As published in Le Monde

Lhe leaders of Latin America meet this week (February 28 – March 2) in Punta del Este, Uruguay to participate in the VIII Regional Platform of the UNDRR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction). This forum is key to addressing the challenges of disaster risk management in the region, strengthening the capacity of nations to respond and prevent disasters through the promotion of effective policies and regional cooperation. This event is critical at a conjunctural moment for the climate security of the Latin American peoples.

Far from being unaffected by natural disasters such as hurricanes, droughts and floods, Latin America has suffered disproportionately from the devastating impacts of these tragic events. These have been reflected in the local economy and social welfare. According to ECLAC, natural disasters cost the region more than 7 billion dollars a year on average[1]. In the coming years these costs will increase exponentially due to climate change.

Months ago, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change announced that the goal of keeping global warming at 1.5°C is “almost unattainable”[2]. Aggressive emissions reduction is critical, but no level of emissions reduction can offset the warming effects of greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere. Under all climate change scenarios, the Earth will continue to warm over the next 30 to 40 years. This is a huge disaster risk that we are not prepared for, posing a huge threat to the most vulnerable people in the region.

Given this bleak scenario, what alternatives do we have? This is where the most recent advances in science and technology come in. In recent years, scientists have reviewed technological approaches derived from processes observed in nature, also known as "climate interventions," as possibilities to rapidly reduce greenhouse gases or global warming.

One such approach is Solar Radiation Modification (SRM) which has shown potential to reduce the risk of natural disasters globally. The most promising SRM techniques involve the scattering of particles in the stratosphere to reflect sunlight directly (Stratospheric Aerosol Injection), or the scattering of particles in marine clouds to make them brighter (Marine Cloud Brightening). These are variations of phenomena we already see in nature. For example, it happens when volcanoes erupt and the particles they emit manage to reduce global temperatures, or as happens now when pollution particles make clouds brighter and create a global cooling effect.

The use of science and technology is one of the main topics of discussion in the UNDRR Region Platform. Consequently, the potential use of SRM for climate disaster risk reduction is an emerging area of interest. A significant number of experts believe that this technology can be an effective tool to mitigate the effects of climate change, especially in the most vulnerable areas. However, there are also concerns about potential negative impacts on the environment and biodiversity, many of them difficult to predict due to a lack of current research. There are also concerns about issues related to transparency and equitable decision-making, particularly in the global south. The best way to understand whether SRM methods are a viable and safe option is through scientific research. The most equitable way to make decisions is with accessible information and inclusive participation in scientific research. Actually, there is no other way to succeed.

It is important that Latin American countries have multiple options to reduce the risk of disaster caused by climate change. It is also important that they can effectively and transparently address the challenges and opportunities offered by SRM technology. The UNDRR Regional Platform should be a valuable space to foster dialogue, cooperation and informed decision-making on climate interventions.

It is critically important to note that SRM technology should not be viewed as a one-size-fits-all solution for disaster risk management in Latin America. It is vital that investment continues to be made in disaster prevention and mitigation measures, such as building resilient infrastructure and promoting sustainable agricultural practices, which are critical to reducing disaster risk. The only way we will be successful in keeping people and ecosystems safe is with a holistic vision and a variety of options to match the challenge we face.

[1] https://www.cepal.org/notas/62/titular02

[2] https://grist.org/climate/the-worlds-most-ambitious-climate-goal-is-essentially-out-of-reach/

Today, criticism of climate intervention, including any research, carries forward the concern that it creates a panacea that will slow greenhouse gas reduction (there is some evidence to suggest that the opposite could be true.) There is also concern that governance may be impossible, though its centralized activities may be far less complex to manage than the diffuse problem of greenhouse gas emissions. (We may even have a model to work from in humanity’s most successful environmental protection effort, The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer.)

Where does that leave us? Governments have declared a climate emergency, but they have not developed strategies to ensure that people are safe and natural systems stable under increased warming conditions over the next 30-50 years.

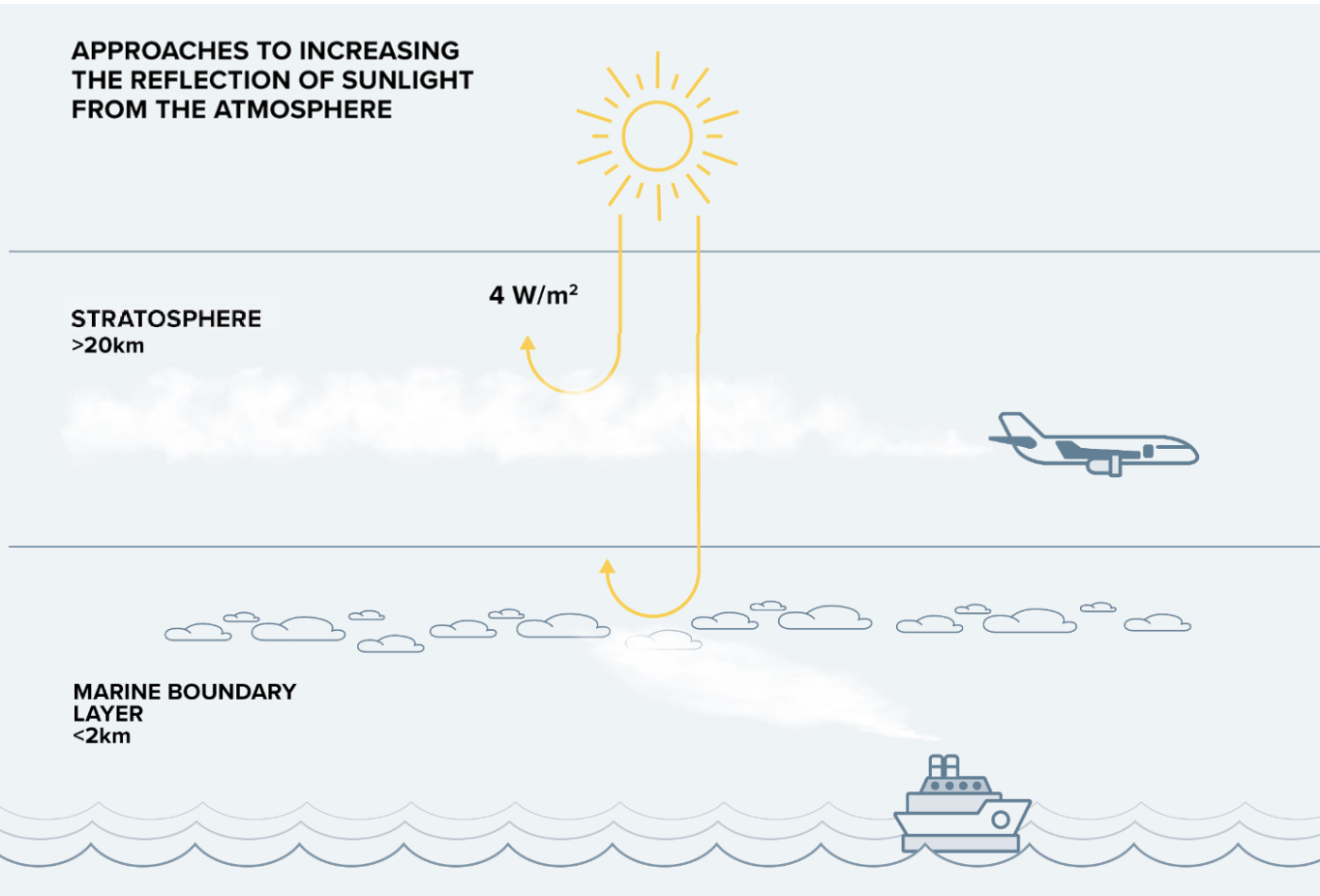

There are escalating private and public investments in approaches for removing greenhouse gas from the atmosphere. If enough is removed, the climate will cool relatively quickly. But in general, these approaches will take decades to scale to the levels required. We may get lucky, but otherwise, our best current failsafe lies in increasing the reflection of sunlight from the atmosphere.

How? The most prominent approaches involve increasing the reflection of sunlight by dispersing a sea-salt mist from ships into clouds over the ocean (“marine cloud brightening”) or releasing particles into the upper atmosphere (“stratospheric aerosol intervention”). (Surface and space-based ideas for reflecting sunlight were discounted in scientific assessments in 2009 and 2015.)

What is the state of play? Recent science fiction novels by Kim Stanley Robinson and Neal Stevensen are terrific reads and get a lot of the science right – except the part where interventions are fast and easy to do. They are capital-intensive to study and scale only with time and money. Dispersing material in the atmosphere is not a solved problem, but it is also not the primary one.

Substantial research is required to evaluate the risks of interventions against projected warming so that policymakers and people around the world can review potential impacts on the climate system and on their communities. The underlying science problem –- the effects of particles (“aerosols”) on clouds and climate –- is one of the largest areas of uncertainty in climate research. Observations and model representations of these processes are far weaker than they need to be, for both predicting climate and for evaluating interventions.

With the right advances, we might develop early warning and response systems for major abrupt changes, similar to the U.S. program in place today to prevent asteroid strikes.

Stepping into an unusual gap, our organization, SilverLining, is advancing crucial aspects of progress. Like a medical foundation, we support research, innovation and policy in a race for objective information to help save lives.

We work with a network of experts to identify the critical requirements - the “roadmap”- for research, which includes both advances in observation and models to better predict near-term climate generally, and programs that integrate technology development and field studies to characterize the effects of particle releases at very small scales so that their effects can be modeled at large ones, including the global climate system, for specific climate interventions.

We operate from the perspective that better information enables better decision-making, and, if widely shared, more constructive politics and more equitable outcomes. To that end, through programs like our partnership with Amazon Sustainability Data Initiative, the National Center for Atmospheric Research and others (deploying, for the first time ever, full climate model simulations on the cloud), we are expanding access to climate models and data for scientists around the world to study climate interventions.

Reducing emissions is imperative. Removing carbon is a critical accelerant to achieving a sustainable climate. But we are approaching an unsafe and unstable environment that may require emergency medicine, and to navigate it safely, we have work to do.